| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

I bims eins baum |

I bims eins baum |

||

| + | ==ich kann alles machen== |

||

| − | ==Substance== |

||

| − | {{Expand section|date=September 2010}}<!---This section misses the most important points of the declaration, and is not genuinely factual. At least its phrasing needs to be checked and improved.---> |

||

| − | The Declaration opens by affirming "the natural and imprescriptible rights of man" to "liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression". It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges by proclaiming an end to exemptions from taxation, freedom and equal rights for all human beings (referred to as "Men"), and access to public office based on talent. The monarchy was restricted, and all citizens were to have the right to take part in the legislative process. [[Freedom of speech]] and press were declared, and arbitrary arrests outlawed.<ref>{{cite book| last = Spielvogel| first = Jackson J.| title = Western Civilization: 1300 to 1815| publisher=Wadsworth Publishing | year = 2008| location = | pages = 580| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=0QKxEJF-zQQC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Man+and+of+the+Citizen&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s | isbn = 978-0-495-50289-0 }}</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | The Declaration also asserted the principles of [[popular sovereignty]], in contrast to the [[divine right of kings]] that characterized the French monarchy, and social equality among citizens, "All the citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents," eliminating the special rights of the nobility and clergy. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Active vs. Passive Citizenship=== |

||

| − | While the [[French Revolution]] provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens. [[Active citizenship]] was granted to men who were French, at least 25 years old, paid taxes equal to three days work, and could not be defined as servants [http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/282/ (Thouret)].<ref>Thouret 1789, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/282/</ref> This meant that at the time of the Declaration only white, male, property owners held these rights.<ref>Censer and Hunt 2001, p. 55.</ref> The deputies in the [[National Assembly (French Revolution)]] believed that only those who held tangible interests in the nation could make informed political decisions.<ref name="Popkin 2006, p. 46">Popkin 2006, p. 46.</ref> This distinction directly affects articles 6, 12, 14, and 15 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen as each of these rights is related to the right to vote and to participate actively in the government. With the decree of 29 October 1789, the term active citizen became embedded in French politics.<ref name="Doyle 1989, p. 124">Doyle 1989, p. 124.</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | The concept of [[passive citizens]] was created to encompass those populations that had been excluded from political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Because of the requirements set down for active citizens, the vote was granted to approximately 4.3 million Frenchmen.<ref name="Doyle 1989, p. 124"/> out of a population of around 29 million.<ref>“Social Causes of the Revolution,” http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/chap1a.html</ref> These omitted groups included women, slaves, children, and foreigners. As these measures were voted upon by the General Assembly, they limited the rights of certain groups of citizens while implementing the democratic process of the new [[French Republic (1792–1804)]].<ref name="Popkin 2006, p. 46"/> This legislation, passed in 1789, was amended by the creators of the [[Constitution of 1795]] in order to eliminate the label of active citizen.<ref name="Doyle 1989, p. 420">Doyle 1989, p. 420.</ref> The power to vote was then, however, to be granted solely to substantial property owners.<ref name="Doyle 1989, p. 420"/> |

||

| − | |||

| − | Tensions arose between active and passive citizens throughout the Revolution. This happened when passive citizens started to call for more rights, or when they openly refused to listen to the ideals set forth by active citizens. This [http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/75/ cartoon] clearly demonstrates the difference that existed between the active and passive citizens along with the tensions associated with such differences.<ref>“Active/Passive Citizen”, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/75/.</ref> In the cartoon, a passive citizen is holding a spade and a wealthy landowning active citizen is ordering the passive citizens to go to work. The act appears condescending to the passive citizen and it revisits the reasons why the French Revolution began in the first place. |

||

| − | |||

| − | Women, in particular, were strong passive citizens who played a significant role in the Revolution. [[Olympe de Gouges]] penned her [[Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen]] in 1791 and drew attention to the need for gender equality.<ref>De Gouges, "Declaration of the Rights of Women," 1791.</ref> By supporting the ideals of [[The French Revolution]] and wishing to expand them to women, she represented herself as a revolutionary citizen. Madame Roland also established herself as an influential figure throughout the Revolution. She saw women of [[The French Revolution]] as holding three roles; “inciting revolutionary action, formulating policy, and informing others of revolutionary events.”<ref>Dalton 2001, p. 1.</ref> By working with men, as opposed to working separate from men, she may have been able to further the fight of revolutionary women. As players in [[The French Revolution]], women occupied a significant role in the civic sphere by forming social movements and participating in popular clubs, allowing them societal influence, despite their lack of direct political influence.<ref>Levy and Applewhite 2002, pp. 319-320, 324.</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Women's rights=== |

||

| − | The Declaration recognized many rights as belonging to citizens (who could only be male). This was despite the fact that after [[The March on Versailles]] on 5 October 1789, women presented the [[Women's Petition to the National Assembly]] in which they proposed a decree giving women equality.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} In 1790 [[Nicolas de Condorcet]] and [[Etta Palm d'Aelders]] unsuccessfully called on the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women.<ref>{{cite book |title=Letters written in France |last=Williams |first= Helen Maria |authorlink= |coauthors=Neil Fraistat, Susan Sniader Lanser, David Brookshire |year=2001 |publisher=Broadview Press Ltd |location= |isbn=978-1-55111-255-8 |page=246 |pages= |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5Ruwz82RicgC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Woman+and+the+Female+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s |accessdate=}}</ref> Condorcet declared that “and he who votes against the right of another, whatever the religion, color, or sex of that other, has henceforth abjured his own”.<ref>{{cite book |title=The evolution of international human rights |last=Lauren |first=Paul Gordon |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=2003 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |location= |isbn= 978-0-8122-1854-1 |page= |pages=18–20 |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=gHRhWgbWyzMC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Man+and+of+the+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s |accessdate=}}</ref> The French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of [[women’s rights]] and this prompted [[Olympe de Gouges]] to publish the [[Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen]] in September 1791.<ref>{{cite book |title=Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933 |last=Naish |first=Camille |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=1991 |publisher=Routledge |location= |isbn= 978-0-415-05585-7 |page=136 |pages= |url= http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OHYOAAAAQAAJ&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Woman+and+the+Female+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s |accessdate=}}</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen is modelled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and is ironic in formulation and exposes the failure of the [[French Revolution]], which had been devoted to [[Egalitarianism|equality]]. It states that: |

||

| − | <blockquote> |

||

| − | “This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society”. |

||

| − | </blockquote> |

||

| − | The ''Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen'' follows the seventeen articles of the ''Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen'' point for point and has been described by Camille Naish as “almost a parody... of the original document”. The first article of the ''Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen'' proclaims that: |

||

| − | <blockquote> |

||

| − | “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.” |

||

| − | </blockquote> |

||

| − | The first article of ''Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen'' replied: |

||

| − | <blockquote> |

||

| − | “Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility”. |

||

| − | </blockquote> |

||

| − | De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law women were fully punishable, yet denied equal rights, declaring “Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker’s rostrum”.<ref>{{cite book |title=Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933 |last=Naish |first=Camille |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=1991 |publisher=Routledge |location= |isbn= 978-0-415-05585-7 |page=137 |pages= |url= http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OHYOAAAAQAAJ&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Woman+and+the+Female+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s |accessdate=}}</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Slavery=== |

||

| − | The declaration did not revoke the institution of slavery, as lobbied for by Jacques-Pierre Brissot's [[Slavery abolition efforts by Les Amis des Noirs|''Les Amis des Noirs'']] and defended by the group of colonial planters called the Club Massiac because they met at the Hôtel Massiac.<ref>The club of reactionary colonial proprietors meeting since July 1789 were opposed to representation in the Assemblée of France's overseas dominions, for fear "that this would expose delicate colonial issues to the hazards of debate in the Assembly," as Robin Blackburn expressed it (Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848 [1988:174f]); see also the speech of [[Jean-Baptiste Belley]]</ref> Despite the lack of explicit mention of slavery in the Declaration, slave uprisings in [[Saint-Domingue]] that would later be known as the beginning of the [[Haitian Revolution]] took inspiration from its words, as discussed in [[C. L. R. James]]' history of the Haitian Revolution, ''[[The Black Jacobins]]''.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} |

||

| − | Deplorable conditions for the thousands of slaves in Saint-Domingue, the most profitable slave colony in the world, also led to the uprisings which would be known as the first successful slave revolt in the New World. Slavery in the French colonies was abolished by the Convention dominated by the Jacobins in 1794. However, Napoleon reinstated it in 1802. The colony of Saint-Domingue declared its independence in 1804. |

||

==Legacy== |

==Legacy== |

||

Revision as of 09:53, 17 January 2020

Template:Distinguish

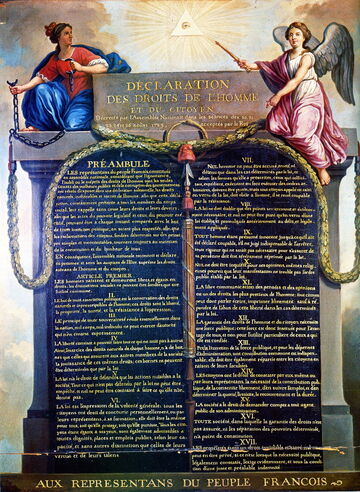

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, approved by the National Constituent Assembly of France, 26 August 1789.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Template:Lang-fr) is a fundamental document of the French Revolution and in the history of human rights, defining the individual and collective rights of all the estates of the realm as universal. Influenced by the doctrine of "natural right", the rights of man are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place, pertaining to human nature itself.

Text

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on 26 August 1799,[1] by the National Constituent Assembly (Assemblée nationale constituante), during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the Declaration was discussed by the representatives on the basis of a 24 article draft proposed by the sixth bureau,[2][3] led by Jérôme Champion de Cicé. The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793 was later adopted.

Articles:

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

- The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

- Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

- Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society. Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law, and no one may be forced to do anything not provided for by law.

- Law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has a right to participate personally, or through his representative, in its foundation. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally eligible to all dignities and to all public positions and occupations, according to their abilities, and without distinction except that of their virtues and talents.

- No person shall be accused, arrested, or imprisoned except in the cases and according to the forms prescribed by law. Any one soliciting, transmitting, executing, or causing to be executed, any arbitrary order, shall be punished. But any citizen summoned or arrested in virtue of the law shall submit without delay, as resistance constitutes an offense.

- The law shall provide for such punishments only as are strictly and obviously necessary, and no one shall suffer punishment except it be legally inflicted in virtue of a law passed and promulgated before the commission of the offense.

- As all persons are held innocent until they shall have been declared guilty, if arrest shall be deemed indispensable, all harshness not essential to the securing of the prisoner's person shall be severely repressed by law.

- No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.

- The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law.

- The security of the rights of man and of the citizen requires public military forces. These forces are, therefore, established for the good of all and not for the personal advantage of those to whom they shall be entrusted.

- A general tax is indispensable for the maintenance of the public force and for the expenses of administration; it ought to be equally apportioned among all citizens according to their means.[4]

- All the citizens have a right to decide, either personally or by their representatives, as to the necessity of the public contribution; to grant this freely; to know to what uses it is put; and to fix the proportion, the mode of assessment and of collection and the duration of the taxes.

- Society has the right to require of every public agent an account of his administration.

- A society in which the observance of the law is not assured, nor the separation of powers defined, has no constitution at all.

- Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of it, unless explicitly demanded by public necessity, legally constituted, demands it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

I bims eins baum

ich kann alles machen

Legacy

The declaration has also influenced and inspired rights-based liberal democracy throughout the world. It was translated as soon as 1793–94 by Colombian Antonio Nariño, who published it despite the Inquisition and was sentenced to be imprisoned for ten years for doing so. In 2003, the document was listed on UNESCO's Memory of the World register.

Constitution of the French Fifth Republic

- Main article: Constitution of the French Fifth Republic

According to the preamble of the Constitution of the French Fifth Republic (adopted on 4 October 1958, and the current constitution), the principles set forth in the Declaration have constitutional value. Many laws and regulations have been canceled because they did not comply with those principles as interpreted by the Conseil Constitutionnel ("Constitutional Council of France") or by the Conseil d'État ("Council of State").

- Taxation legislation or practices that seem to make some unwarranted difference between citizens are struck down as unconstitutional.

- Suggestions of positive discrimination on ethnic grounds are rejected because they infringe on the principle of equality, since they would establish categories of people that would, by birth, enjoy greater rights.

Conspiracy theories

The Eye of Providence represents the sun 'shining' on the laws and fueled several conspiracy theories, for instance that the French Revolution was caused by occults groups.[5][6]Template:Better source

Other early declarations of rights

- Poland: Henrician Articles and Pacta Conventa (1573)

- England: Magna Carta (1215), Bill of Rights of 1689

- Scotland: Claim of Right (1689)

- United States: United States Bill of Rights (1791)

See also

- Human rights in France

- Moral universalism

- Natural law and natural rights

- Universality

References

- Georg Jellinek, Die Erklärung der Menschen- und Bürgerrechte, Duncker&Humblot, Berlin, 1895.

- Vincent Marcaggi, Les origines de la déclaration des droits de l'homme de 1789, Fontenmoing, Paris, 1912.

- Giorgio Del Vecchio, La déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen dans la Révolution française: contributions à l’histoire de la civilisation européenne, Librairie générale de droit et de jurisprudence, Paris,1968.

- Stéphane Rials, ed, La déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, Hachette, Paris, 1988, ISBN 2-01-014671-9.

- Claude-Albert Colliard, La déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen de 1789, La doumentation française, Paris, 1990, ISBN 2-11-002329-5.

- Gérard Conac, Marc Debene, Gérard Teboul, eds, La Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789; histoire, analyse et commentaires, Economica, Paris, 1993, ISBN 978-2-7178-2483-4.

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Susan Dalton, Gender and the Shifting Ground of Revolutionary Politics: The Case of Madame Roland, «Canadian Journal of History», 36, no. 2 (2001): 259-283.

- Realino Marra, La giustizia penale nei princìpi del 1789, «Materiali per una storia della cultura giuridica», XXXI-2, 2001, 353-64.

- Jack Censer and Lynn Hunt, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

- Darline Levy and Harriet Applewhite, A Political Revolution for Women? The Case of Paris, In The French Revolution: conflicting interpretations. 5th ed. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger Pub. Co., 2002. 317-346.

- Jeremy Popkin, A History of Modern France, Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, Inc., 2006.

- "Active Citizen/Passive Citizen, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/75/ (accessed October 30, 2011).

- Jacques–Guillaume Thouret, Report on the Basis of Political Eligibility" (29 September 1789), Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, accessed October 26, 2011 http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/282/.

- Olympe de Gouges, Declaration of the Rights of Woman, 1791, College of Staten Island Library. http://www.library.csi.cuny.edu/dept/americanstudies/lavender/decwom2.html (accessed October 30, 2011).

- “Social Causes of the Revolution” Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, accessed October 26, 2011, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/chap1a.html.

Further reading

- Gary Kates and Olwen Hufton. "In Search of Counter-Revolutionary Women." The French Revolution: Recent Debates and New Controversies. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Robin Blackburn, “Haiti, Slavery, and the Age of the Democratic Revolution” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 63, No. 4, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, October 2006. 643-674.

- Immanuel Wallerstein. 2003. Citizens all? Citizens some! The making of the citizen. Comparative Studies in Society and History 45, (4): 650, [7] (accessed November 3, 2011).

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen translated into Austrian übertragen by the deaf actor and translator Horst Dittrich, edited by ARBOS – Company for Music and Theatre, ISBN: 978-3-9503173-2-9, ARBOS-Edition © & ® 2012[8]

Notes

- ↑ Some sources say 27 August because the debate was not officially closed.

- ↑ The original draft is an annex to the report of the August 12th report (Archives parlementaires, 1,sup>e série, tome VIII, débats du 12 août 1789, p.431).

- ↑ Archives parlementaires, 1e série, tome VIII, débats du 19 août 1789, p.459.

- ↑ "Declaration". http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/declaration.html. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ↑ Mounier, Jean Joseph, On the Influence Attributed to Philosophers, Free-Masons, and to the Illuminati on the Revolution of France, facsimile reproduction with an introduction by Theodore A. DiPadove. Delmar, New York, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, 1974, p.69.

- ↑ Knight, Peter (2003). Conspiracy theories in American history : an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 226–227, 336–337. ISBN 978-1-57607-812-9. http://books.google.fr/books?id=qMIDrggs8TsC&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ http://search.proquest.com/docview/212669823?accountid=14608

- ↑ http://vimeo.com/52676206

External links

Template:Sisterlinks

- "Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen de 1789" (in French). Conseil constitutionnel. http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/francais/la-constitution/la-constitution-du-4-octobre-1958/declaration-des-droits-de-l-homme-et-du-citoyen-de-1789.5076.html. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen de 1789" (in French). Légifrance. http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/Droit-francais/Constitution/Declaration-des-Droits-de-l-Homme-et-du-Citoyen-de-1789. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen de 1789" (in French). Ministère de la Justice et des Libertés : TEXTES & RÉFORMES. http://www.textes.justice.gouv.fr/textes-fondamentaux-10086/droits-de-lhomme-et-libertes-fondamentales-10087/declaration-des-droits-de-lhomme-et-du-citoyen-de-1789-10116.html. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Declaration of human and civic rights of 26 August 1789". Conseil constitutionnel. http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/root/bank_mm/anglais/cst2.pdf. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

Template:French Revolution navbox